Music Education in Spain

II. School System and Structure

III. Music Education in Schools

V. Critical Comment and Future Development

I. Political Framework

According to the constitution passed on 6th December 1978 Spain is a social and democratic state under the rule of law and has the form of a parliamentary government under a constitutional monarchy. The constitution limits the role of the monarch largely to representational functions. Functions performed by the king that go beyond this include ratifying laws and the appointment and dismissal of the head of the government (Presidente del Gobierno). The supreme legislative body in Spain is the parliament (Sp. Cortes Generales) which is divided into two houses: the Congress of Deputies (Congreso de los Diputados) and the Senate (Senado). Spain is politically organised into 17 autonomous communities or regions (comunidades autónomas) and two autonomous cities (ciudades autónomas) in North Africa: Ceuta and Melilla.

II. School System and Structure

In Spain, state-run schools coexist with private and semi-private schools. Although the majority are state-run, the number of semi-private schools (Sp. Centros Concertados), which are normally maintained by the Church, should not be underestimated.

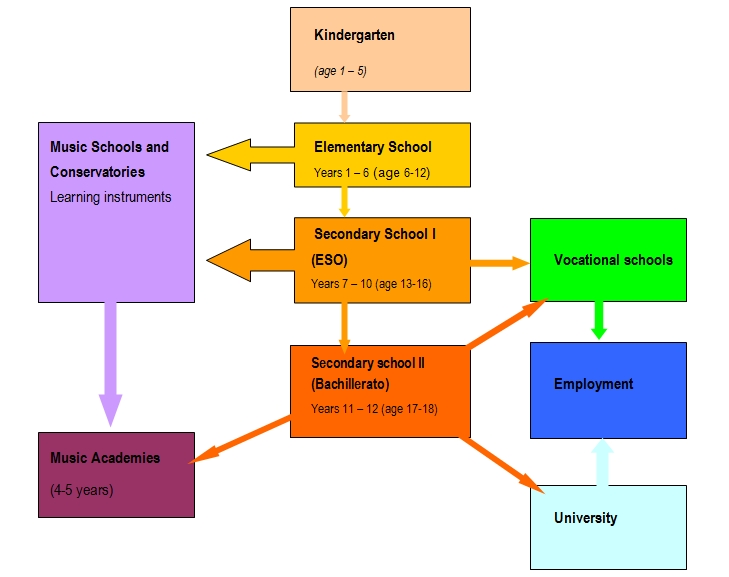

The school structure is composed of a six-year primary level (Educación Primaria), a four-year lower secondary level (Educación Secundaria Obligatoria) which is organised in the form of a comprehensive school, and a two-year upper school (Bachillerato). The Spanish conference of arts and education ministers has reached agreement on only very vague nationwide standards. It is therefore left to the various Comunidades Autónomas to work out the details of the curriculum and develop it. As regards music as a school subject there are no significant regional differences.

III. Music Education in Schools

It is only since 1990 that music has been a compulsory school subject in grades 1 to 6 of the elementary school and grades 7 and/or 8 of lower schools in every one of Spain’s autonomous regions. The number of music lessons in each grade is as follows:

· Elementary school (grades 1-6): one lesson a week for all six grades.

·

Lower school:

- Grades 7 and 8: two lessons a week in some autonomous regions (e.g. Andalusia ). In other regions there are four lessons a week in only one of the two grades 7

and 8. In this case it is up to the school to decide whether it offers music in

the 7th grade or the 8th grade.

- 9th grade: no music.

- 10th grade: three lessons a week. In this grade, music is optional for the

pupils.

· Upper school (grades 11 and 12): music is offered only as one

optional subject among others (literature, visual arts, applied anatomy) for

pupils choosing the Bachillerato de Artes. Pupils taking this option

have the opportunity to choose one or more of the following four options (all

four lessons a week):

- musical theory and musical practice

- history of music and dance

- analysis I,

- analysis II.

School-leaving examinations with university entitlement that consist of tasks set centrally by national ministries for all schools in Spain do not exist. This means that there is no obligatory core curriculum for the upper schools. For the subject of music this means for instance that there is no set canon of musical works that must be covered. Each school decides itself what should be included in or excluded from its curriculum (Proyecto Curricular de Centro). The differences between individual schools are consequently very large.

Secondary schools that place particular emphasis on music are few and far between; nor is there any particularly great concentration on music education at elementary schools. However, several schools offer extra-curricular activities in the field of music (learning an instrument, choirs, bands, dance), some of which the pupils have to pay for themselves. Cooperation with municipal and/or private music schools, or, in rural areas, with music societies and ensembles would be desirable here.

IV. Music Curricula

The autonomous structure in Spain means there is no national curriculum. Instead, a number of different basic frameworks (Diseños Curriculares Base) exist, some of which differ again according to the type of school.

There is a kind of consensus among education experts and those concerned with education policy that music as a subject in general school education does not have the sole, or even primary, objective of creating the opportunity for musical activity and promoting it (singing, playing an instrument, playing in school bands), but must in equal measure foster knowledge of music and its cultural and historical contexts. Whether the coming years will see a nationwide simplification of the music syllabus in schools as part of the development of standards is doubtful, however.

The Diseños Curriculares Base in every region contains a total of six topics for the Educación Primaria. One of these is Educación Artística, of which music is just one part. Article 4 of the Decree for Andalusia that deals with elementary education cites the general learning objectives relating to Educación Artística that schools must include in their curriculum. These are, among others:

· active listening,

· visual and aural recognition of several musical instruments and of female, male and infant voices,

· repetition (AA) and contrast (AB) in songs and other musical works,

· use of the voice, body and various objects as musical instruments,

· recitation and singing (by heart) of single-part songs and series,

· simple dances,

· graphic notation,

· improvisation of rhythmical and melodic patterns.

Later, in Educación Secundaria, the learning objectives of Educación Primaria are extended. For example, the Andalusian Ministry of Education formulated the following eight objectives for music education that is not taught as a subject in its own right until secondary school:

· learning to appreciate the importance of silence as a prerequisite for the existence of music,

· acquiring the ability to express ideas and feelings with the aid of the voice, instruments and movement,

· the ability to appreciate musical works as a means of aesthetic expression and aesthetic communication,

· the ability to use various different forms of musical expression unaided,

· the ability to use dance and movement as means of portraying images, feelings and ideas,

· analysis of musical works that are classified as part of the regional, Spanish and universal cultural heritage,

· participation in musical activities at school and outside it,

· development of personal standards and value judgements for music.

In Bachillerato (= final exam to get the universities degree after secondary education II) these learning objectives are further extended: “The theory and practice of music enable pupils to deepen their musical knowledge. This subject is based on two pillars. Firstly, continued education in the morphological and syntactic elements of music. Secondly, the development of skills relating to musical expression: fashioning and practising music.”

V. Critical Comment and Future Development

According to a number of studies there is a relevant discrepancy between the music lessons stipulated in the curriculum and actual music lessons taught at schools in Spain. Schools that give music a central place in their curriculum are rare indeed. The main problem is the insufficient (or inappropriate) training of future music teachers. Incomprehensibly the higher education reform after Bologna will only exacerbate the problem. From 2010 the current degree course Training of Music Teachers for Primary Schools will be discontinued while music teachers at secondary schools will receive a four-year training course as pure musicologists. The latest implementation of the LOE bill relating to the school-leaving examination in Andalusia provides a good example of this already outdated conception of music education in Europe: here the entire curriculum will concentrate primarily on a chronological overview of “serious” European music.

The advice and recommendations given by music teachers and music education bodies from Spain and other countries over the past few years have been systematically ignored by the Spanish authorities. These political measures will lead to a decline in music education in Spain. On the other hand a number of things have been accomplished in the past few years that lead us to hope that a genuine standardisation of our subject within the European Union will not stay merely a utopian vision. That is reason enough to continue the fight.