Music Education in Schools

Conclusion

Time Allocations for Music Education

Issues for the Curriculum in Practice

Examples of Practice in Context

These conclusions aim to draw attention to certain aspects and themes drawn from the descriptions of music education in the 20 countries represented in the meNet project. The texts have been written by partners who have in some cases also taken responsibility for researching and describing music education in the school systems of European countries that are not represented by any active meNet partner. In these cases the detail is inevitably less rich but contributes usefully to the scope of the task. Whilst every effort has been made to verify the accuracy of the information collated for this document it should be noted that, by the time of publication, some changes may have occurred due to policy initiatives or revisions. It should also be noted that the research was undertaken in accordance with the meNet Ethical Statement

School Structures

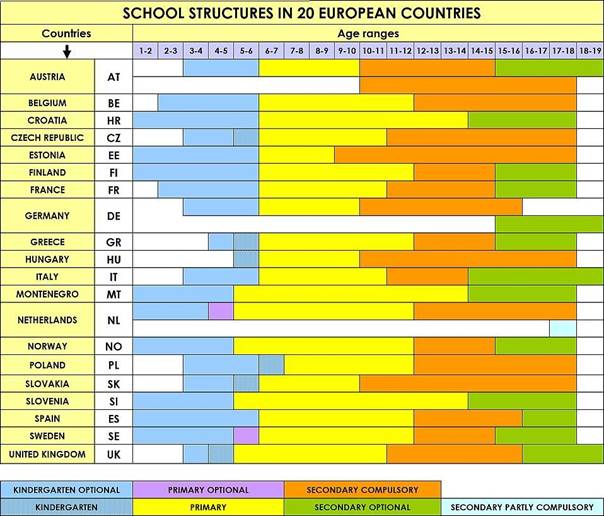

Any understanding of Music Education in the countries surveyed must at first consider the organisation of statutory schooling. The chart below shows how the structure and duration of schooling are organised. Further detail can be found at the Website of EURYDICE.

This table makes clear that there are differences in the age ranges covered by “primary” and “secondary” education. Thus, the starting age for compulsory schooling and the age at which children transfer to secondary education varies across these countries. There are also variations in the overall duration of compulsory education. Hungary and the Czech Republic have the longest period of 13 years. The majority start compulsory schooling at the age of 6 years, with all offering optional pre-school provision: from the age of 3 in eight countries and from the age of 1 in nine countries. Music is included as a compulsory subject for the primary age range in every country. However there is some variation in secondary schools with compulsory music most common up to the age of 14 and optional after this age.

Further comparative investigation might be undertaken to consider how the structures and extent of school based education affect the musical education of young people: How does the length of time spent in school support or hinder musical development? How does the age of transition from one phase of schooling to the next impact upon music learning? What effect does the amount of time spent in pre-school/kindergarten have on children’s music development?

Valuing Music Education

In all twenty countries, Music is included in compulsory school curricula. Curriculum documents often include a statement on the value and importance of the subject in the education of all young people. The values ascribed to music education can be separated into three broad groups:

1 intrinsic values associated with the development of musical skills, knowledge and understanding necessary to make and respond to music,

2 knowledge, understanding and appreciation of cultural environment and heritage and

3 the contribution Music makes to the development of the individual and to communities through creativity, identity formation, personal development, and social interaction.

A few curricula give a view of Music as an integral part of arts or cultural education alongside Visual Art, Dance and Drama, see for example, The Netherlands, Germany and Poland. Whilst falling short of this intention some curricula emphasise Music’s close relationship with Dance, especially for primary age children, for example in Norway .

There appear to be two, possibly interconnecting, motives for this:

1 the view that Music should be seen in the broader domain of the Arts as a distinct field of knowledge,

2 a reflection of the value of cultural heritage in which traditional music and dance play a significant role. Dance and movement are referred to in almost all the texts related to the primary phase, often as a means to developing rhythmic skills.

The value of lifelong learning is also mentioned in various ways, such as, developing positive attitudes towards music (Finland and Greece); and the motivation to participate in music-making and to be an audience for Music (England, Estonia, The Netherlands, Scotland)

Examples of curriculum statements of the value and importance of music can be found for Austria, and England.

Time Allocations for Music Education

Whilst music always features in school curricula, time allocation for music within the school timetable varies across the age ranges, as can be seen in the following tables.

Compulsory Time for Music Education

The following three diagrams show the time allocations for compulsory music lessons in Kindergarten, Primary and Secondary school.

There are often national guidelines for the amount of curriculum time allocated to music but it is mostly the case that individual schools have a good deal of discretion as to the amount of time devoted to Music. Indeed there are some countries in which there is no compulsory allocation of time for Music. In some countries, particularly in the primary sector time for music may be dependent on the presence of confident generalist teachers or specialist teachers for Music; and on the degree of pressure placed on schools to focus on ‘core’ subjects such as language and mathematics.

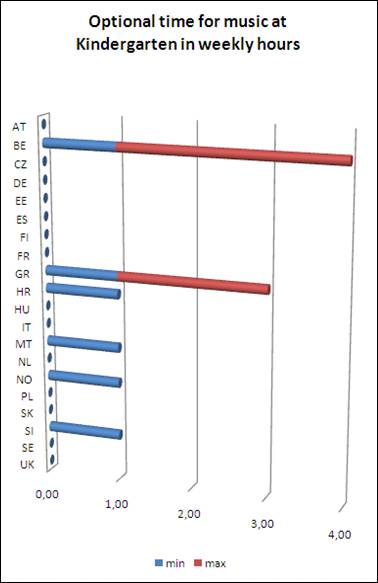

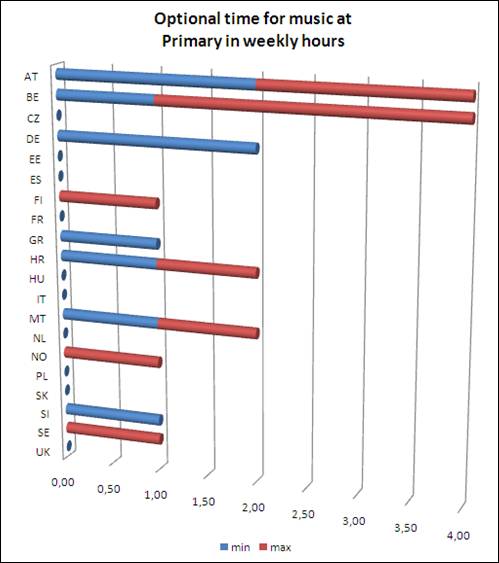

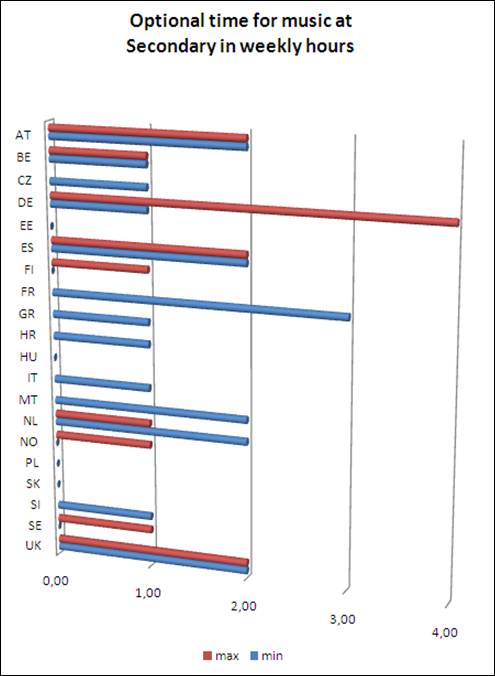

Additional and Optional Time for Music

As mentioned earlier, most countries provide for regular contact with music education in the classroom from entry into the school system up to the early teenage years.

In a minority of countries students continue with some compulsory arts education at the higher levels of secondary – usually choosing between Art and Music (e.g. Austria, Czech Republic, Slovakia, The Netherlands)

However schools in some countries are able to offer additional lessons as an option. The Czech Republic has 40 Primary schools with extended music education. In these schools music education is taught for 4 – 6 lessons per week. Local determination of the amount of music available would also appear to be the norm in Hungary where there is one compulsory singing lesson per week but a few schools will supplement this with an extra dance or choral lesson for all, and some may add “higher standard classes”. Finland, Norway and Sweden , for example, follow a different pattern: in these countries the number of hours for music education are prescribed, but individual schools can decide whether these hours will be spread evenly across the time in school or concentrated within a smaller time- scale, e.g. in one school year.

Schools in all countries commonly offer musical activities as part of the extended curriculum, outside of the normal timetable. Vocal and intrumental ensembles are a common feature of school life and in some countries choral activity is partciularly strong (see Estonia, Slovenia) and in Italian secondary schools there are additional music lessons in the afternoons, for one hour per week on vocal or instrumental ensembles and orchestras.

In most countries upper secondary students (those aged 14/15 and older) can study Music to a more advanced level as part of graduation examinations ( matura; abitur; A Levels) and for progressing to music studies at university. This usually happens within the normal upper school timetable but in a small number of countries there may be more specialist schools at which students can do advanced studies in Music (see, for example, Finland and Sweden and Slovenia).

As mentioned above, in most countries arts and cultural education for all students ceases by the age of 16 (in some cases as early as 14). Given the strong statements made in curriculum documents about the value and importance of Music in education (and the Arts in general) this early end seems contradictory.

The problem of time for music is experienced everywhere and solutions vary. Alternative routes for the musically enthusiastic or able; additional music activities out of normal school hours are typical. More research is needed to ascertain to what extent such approaches address access for the disadvantaged.

Here are the three diagrams showing optional time allocations for music education in Kindergarten, Primary school and secondary school:

Further Specialist Music Education

In the majority of European countries there exist state or privately funded music schools which provide instrumental tuition and classes in music theory, aural skills etc. This means that there are, in effect two music education systems running in parallel, with the more specialist tuition available to those who can access it. In some countries this provision is free for all who want it; in others it is only available to the musically able, and in others parents may have to pay. For more information see the pages of the European Musicschoolunion.

Such music schools operate after school and at weekends like it is the case in Belgium. A significant change in music education in Germany and Greece arises from the increasing trend towards all-day schools which will impact on the specialist music schools that take place during afternoons. In England instrumental tuition is available free or subsidised by the state through Music Services who provide tutors who visit schools to teach individuals and groups. There are also a small number of specialist music schools which function as an alternative to ordinary school.

We have not looked specifically at the effect of this provision on music in statutory schools. Further research would be of value: How does the specialist music school affect attitudes to music in ordinary schools? Do music teachers from both these types of institutions collaborate in discussions on, for example curriculum; on learners’ progress, on complementary approaches? What is the experience of young people who are accessing both forms of music education simultaneously?

Curriculum Content

There is no consistent way in which curriculum documents construct and present aims, content or learning outcomes for music. Some documents articulate a clear philosophy and purpose for music education and are less concerned with defining specific content. Others give detailed lists of the musical skills, knowledge and repertoire to be taught in clear sequence across the ages. Most documents attempt to incorporate statements about ways of learning, focusing on procedural knowledge (for performing, composing and listening) and understanding of social and cultural contexts for Music; and statements which are more focused on acquiring the skills of music making through singing; playing instruments, learning notation and theory. Although improvising and arranging are often mentioned, in the context of developing rhythmic and melodic skills rather than as an end in themselves, composing (especially in primary years) is less usual.

Listening and responding to Music, learning about music and becoming critical are features of most curricula. Few curricula require a comprehensive study of music history (e.g. like in Germany, Croatia and Estonia) while most make references to music of the past or heritage; or the development of music without much detail.

Whilst many countries’ curriculum documents deconstruct music education into the basic activities of music making: composing, performing, listening and understanding, an holistic and integrated approach to music education is almost always advocated. Some documents make strong statements about the importance of integrating the activities, knowledge and understanding of music in order to make learning meaningful (see, for example, Austria).

Only a minority of countries give an emphasis on integrating music with other arts subjects (Germany, Czech Republic, Slovakia, Austria, Poland). The Netherlands goes further and outlines themes and topics for cross curricular learning. In Greece, cross curricular links are encouraged throughout the whole music curriculum.

We know from experience that there are often gaps between the stated aims and objectives presented in such documents, and practice. The process of writing a curriculum document is a valuable and educative one for those involved and one can detect the quality of thinking and care with language. What we have not explored in detail is how such guidance translates into the day to day experiences of teachers and their students in music lessons.

Styles and Traditions

All curriculum documents make reference to the importance of becoming familiar with the music of one’s country’s culture and cultural heritage. In some countries traditional music, songs and dances form a significant part of the curriculum: for example Estonia has a particularly strong tradition in choral singing which is fostered throughout the school years and every school has at least one choir. The nurturing of national identity through the music curriculum is a central to the aims for music education in several countries for example in Slovakia students are expected to be able to dance Eastern European folk dances such as the Polka and Czardas and in Montenegro knowledge of national musical heritage is emphasised. InHungary musical material used especially in the early years is drawn from Hungarian folk music.

Music is also often seen as a means for developing wider cultural understanding through engagement with music from around the globe. This is articulated in curricula of half the countries in this survey although usually as an all embracing phrase such as ‘the music of different cultures’ and rarely with reference to any particular musical traditions.

In almost all curricula the performance, study and appreciation of art music increases in prominence as students mature. With a few exceptions jazz and popular music is included but not given the same emphasis as art music. Sweden is the only country where the curriculum makes no reference to any particular styles or musical traditions.

Notation and Theory

The requirement to teach staff notation and music theory varies greatly. Some documents give detailed lists of theoretical content for every age phase; others say very little. Those curricula that are explicit in emphasising European traditions through folk and art music tend also to require particular attention to these aspects.

Graphic notation is mentioned in many documents both in the context of primary music (perhaps as a precursor to traditional notation) and for secondary music where it may be used for alternative and contemporary music study and creative work.

Music Technology

Less than half the countries’ curricula make explicit reference to the use of digital technology. Sweden and all four education systems in the UK expect students throughout their schooling to be using such technologies across all subjects; and in music, especially in secondary schools, its use is well established. In most countries it is more often mentioned in relation to secondary school music and includes the use of keyboards and recording. More extensive use is likely to be linked to the availability of funding as well as, perhaps, the degree to which the curriculum promotes contemporary and popular music; or where there is an emphasis on composing.

Without significant investment by governments the development of music technology use in schools is likely to be very slow. In such situations the availability of digital technologies for music making and downloading in the home may create difficulties for school music teachers in engaging students and making music learning relevant.

Progression and Learning Outcomes

Progression in music learning is expressed through increased range and complexity of musical skills and knowledge, and in the broadening of styles and repertoire covered. It is evident that many curricula recognise and acknowledge the needs of young teenagers with statements about identity formation and the importance of understanding music in its social and cultural context. Very few curricula include learning outcomes – and where these exist they tend to cover two or three years at a time, like it is the case in the curricula for the UK; Slovenia, Greece, Norway, Sweden and Finland.

Issues for the Curriculum in Practice

In reading each country’s document one can find many common topics, approaches and emphases. However one can also find that there are great disparities in comprehensiveness and ‘strength’ of the curriculum documents. Of course the weight of the document does not necessarily mean that the quality of music education in schools is of equal weight but it does, at least indicate recognition and intent. Whether one agrees with the notion of national directives or guidance or not, one can see clearly, through this evidence, that music in schools is underdeveloped in a minority of countries.

Spain, for instance, has an underdeveloped national curriculum for music and has just introduced changes to teacher education programmes which will mean the end of specialist primary music teacher training. At secondary level, a bachelor's or master's degree in musicology or instrumental music is required. Future secondary music teachers must either complete a university degree course in musicology or have graduated as a musician from an academy of music. This means there is still no course at tertiary level in music education or music didactics for secondary music teachers and no such course is planned in the future. In Greece there is a need to further develop the training of specialist music teachers with more focus given to music educational issues, especially in the primary phase.

Many countries follow a policy of generalist teachers in primary. Such teachers are required, in principle, to teach all curriculum subjects. However where training for music is limited teacher may lack the confidence to teach music successfully. In such a situation there can develop great variations in the quantity and quality of music teaching in different schools. Some schools may invest in a specialist teacher, others not. Again the contradiction of curriculum statements declaring the importance of music education for young children in terms of their overall physical, social and emotional development and this lack of vision in providing appropriate teacher training is a concern.

Examples of Practice in Context

In order to exemplify some of the practice to be found in partner countries some examples are offered on the meNet Website. These show recently completed musical projects and initiatives undertaken in primary and secondary schools. You will find more detailed descriptions as well as media inside the Website-Area Examples of Practice in Context.

1 AT – Light Painting with Music. This example from Austria describes how new media is used to combine the fields of music, movement, location design, photography and art, thus providing opportunities for interdisciplinary activities. In addition, it provides a tool for analysis in music education that reveals the style and structure of the music on the basis of an emotional impression.

2 AT – Klangnetze . Inventing the world with your ears – A way to introduce contemporary music in schools. This example from Austria shows how working with a composer in residence can transform students understanding of contemporary music and introduce them to a way of learning where the process is of equal importance to the outcome.

3 DE – The “WDR Brahms Project” – Students take the plunge as music journalists. This example from Germany shows how working with an artistic institution can develop in depth musical understanding and develop literacy and oracy skills.

4 DE – “Sounding Stones” . This example from Germany is similar to “Klangnetze” but the sound sources used are not traditional instruments and the musical work can lead to learning in other subject areas.

5 DE – “Move”. Theatre of Music and Movement. This example from Germany shows how development of a music theatre piece can be used to develop learning and participation in a special school.

6 ES – Beyond the Sound . Socialising through music at school. This example from Spain shows how through engaging in music activities students at risk from dropping out from education can be kept within the system and how a school can transform itself.

7 SI – Re-telling Fairy Tales . Preparing students in a vocational school for arts based practice in non school settings. This example from Slovenia shows how combining music with other art forms can develop wider performance skills which can be used in vocational settings.

8 SI – Integrating Folk Music into the Primary Music Curriculum. This example from Slovenia shows how the folk tradition can be preserved through introducing fold music and dance into the music curriculum

9 SK – Superclass . Supporting cultural education in schools. This example from Slovakia shows how the status of music education in schools can be raised, how music can be combined with ICT and how participation in musical activity can improve students’ social skills

10 UK – Gigajam . Secondary school students composing songs using technology. This example from England shows how an English secondary school uses the GIGAJAM program (http://www.gigajam.co.uk ) to help students compose songs.

11 UK – Raising student attainment in music through specialist schools. This example describes a government strategy to improve attainment in all secondary schools in England through specialising in particular curriculum areas. The example of one music specialist school is presented.

Further Work

This study is but a snapshot of Music Education in 20 European countries. The music educators involved in this task believe it is a good starting point for more in depth work. meNet has established that music education is, for the most part, thriving across Europe and that there are many examples where music is being used to improve the life chances of young people. Establishing a network of interested teachers who can share pedagogical approaches used in music education, share practice and develop new joint projects will undoubtedly result in even stronger music education for future generations.

|

|

|